AND EMRs

It was hour 22 out of a potential 36 hour-long shift. Medical students, during third and fourth year, can be worked up to 36 hours straight without any legal backlash. The thought of this kept interrupting my sleep-deprived mind, halting my attention and shifting it away from the reading I wanted to get done before I had to do the entire shift over again the next day. Granted we were excused to return home for 6 hours to eat and sleep–they allowed us those minute luxuries–before heading back to resume the same drudgery on repeat.

I was seated next to six general surgery residents upstairs, and there was only one other medical student, a classmate, on the same exhaustive shift as the rest of us. All eight of us studied our screens still in silence, some of us too caffeinated and others not enough, across from the also never-resting glares of our computer screens which faithfully displayed our currently admitted patients on Epic—the almost universally employed Electronic Medical Record system. I was hoping by continually refreshing the home page or a phone call would bestow upon us the chance to escape the austerity suffocating the company of each other, would interrupt my attempts to absorb the linear words covering the pages of my textbook; there was no hope of me learning anything at this point and boredom became a dull aching symptom of this shift every night once 2 am rolled around. It was now 2:15. Then 2:30. The minutes were dragging mocking my exhaustion and reminding me, “you’ve got only 3 hours left until you have to pretend you’re not exhausted but jubilantly thrilled to enjoy this incredible privilege few are allowed to experience while internally cussing the residents and attendings as we treaded from patient room to patient room over the span of two hours during rounds…remember to prepare for any question they might ask you! Remember that these attendings will pimp you in front of the 4 other medical students who will show up for their shift at 5 am! LOL.”

I needed to get some of these words staring back at me from the page to sink in. The gallbladder…the pancreas. Two of my least favorite organs since they both tended to pull whatever shit they felt inclined to do so and mimicked the symptoms of all other abdominal organs. Pancreatitis, cholestasis, cholecystitis–my least favorite medical conditions. The symptoms differentiating them were so minute I really didn’t even care to learn about them.

Finally a device remembered now nostalgically as a landline telephone—an ancient relic sometimes seen in contemporary society mostly in hospitals and waiting rooms or your grandmother’s pungent house complete with a bowl of those strawberry candies no one else has ever once seen for sale at any grocery or 99 cents store—rang deeply and monotonously: an ornery tone. On the other end was one of the surgery interns who had 10 minutes previously left our cramped room to go check on his patients—or, more likely, attempted to find some form of respite from this stiff crowd of tired individuals.

On “nights” during general surgery, any page usually came from an ER physician requesting a consult—some ER resident who found an opportunity to pass the torch to some other resident in a different department and rarely did an emergent surgery ever result from such a consult. The surgeons would usually complain about this on our way down to respond to the page, grudgingly, and rightly so. The ER MDs were just as tired as the specialists but they had the option to defer action and shirk responsibility. If they didn’t have to deal with it–if it wasn’t a gunshot wound or a simple cut that required sutures–they would page infectious disease over a cold or surgery if a patient had diarrhea so they could continue sitting on their asses playing on their phones.

Thus we got paged for every headache or stomach pain. “Might be appendicitis,” the ER docs would say as if to justify their call. So we’d make the trek across the hospital at any hour of the night and morning to appease the ER residents, who when you were sleep-deprived, annoyed the fuck out of you with their laziness and immature shift of responsibility to whoever they could think of, any other MD because they knew any specialist resident would have to respond and take the responsibility for the patient the ER doctor should be caring for. So we’d walk past the ER residents, their feet up on their desk, on their phones watching videos, to provide a patient with whatever relief from “impacted bowels,” in layman’s terms constipation, which usually proved to be the underlying pathology. That was the “potentially life-threatening abdominal pain” ER would page surgery about for a “second opinion.” Granted sometimes a gunshot victim came in and that would suck to deal with but still, dude, constipation does not require a second opinion from surgery.

So the phone rang and indeed it was one of the surgery interns saying that he had just gotten a consult from the ER and would I and the resident to which I was assigned meet him in the ER. Of course. What was going on? He laughed. “I’d read up on the patient’s chart before you come down though.” “Well yeah but what’s so funny?” “You’ll see.” He made one last chuckle and then click. Confused but somewhat excited for the possibility of a particularly interesting case, we dragged our clogs down to the ER through the intricate maze of badge-protected corridors and hallways that architecturally made no sense and finally passed through the last automatic double door, and magically appeared in the ER. If I had been asked to find my way back alone I would’ve probably lived out my last days wandering the corridors of that hospital. I just followed my resident, who was always several steps ahead of me–never did we share a conversation–and hoped I didn’t fall asleep or lag behind far enough to where she’d turn a corner and be gone. Then I’d be screwed. So when finally the last set of doors opened and we were magically inside the heart of the the ER it seemed we had indeed fallen down the rabbit hole and into a sea of unexpected non-chaos. We passed all the residents, not once sharing a glance or making eye contact and plopped ourselves down in front of two computers next to each other. “Ok tell me what you find and I’ll look up the patient’s chart too. Last name is such-and-such MRN # 1234567.” We sat in what seemed like even more silence than we had shared before which lasted several minutes as we both poured over the ER resident’s admission note, the patient’s vitals, any labs that had come back, and the last 5 notes that had been written in Epic after previous medical encounters with this patient we were about to meet.

Well this was an interesting case but not for the reasons we were expecting. This wasn’t some episode of House, some perplexing and rare medical anomaly–a mysterious puzzle involving a vaginal tick and seizures. But there were an abundant amount of discrepancies in the patient’s medical chart, from one note to the next, and there were too many incongruences to make any sense of who we were about to meet.

First there was the patient’s name on top of the patient’s listed “gender,” which was displayed, as always, in the upper left corner of the EMR (electronic medical record.) When you pull up any patient on Epic, his or her name will appear in the top left and underneath the name will be his or her DOB (date of birth) and under that the letters XX or XY, indicating if the patient was female or male respectively. This was meant to be a broad overview of the patient—basic patient “identifiers,” as they are called in the world of medicine. Before reading any of past medical notes stored on the system or examining any labs or diagnostic images, the gender and the DOB serves to jumpstart the assigned MD’s cognitive process. The name, the DOB, the “gender” immediately invokes learned medical facts regarding associated risk factors based mostly on sex and age.

In fact, almost every medical note begins with something similar to the following: “Mr. Joffrey Baratheon is a 16 year old Caucasian male who presents with foaming at the mouth and bleeding from multiple facial orifices after consuming a glass of red wine. Of note, according to the patient’s fiancé, several of his acquaintances ‘have reason to want the patient dead.’ Significantly, the patient is the product of an incestuous relationship as his parents are siblings.” Something along these lines.

So each note starts with “identifiers” to call to mind any relevant risk factors—age, sex, race—as men and women, the young and the elderly, and different races of people carry personalized risks of developing certain medical conditions. This isn’t meant to subject patient’s to inequity or prejudice but are meant to ensure the polar opposite of unethical mistreatment: medically objective information regarding key risk factors that are essential in providing the most optimal medical care possible for each individual patient. Tailor a patient’s treatment around his or her risk factors and past medical history to help secure the best health outcomes of each patient as an individual.

Many readers already see where this is going, so I continue.

Our patient’s medical chart displayed a conventional female name but “XY” underneath it. Already I my thoughts whirled: was the name incorrect or was the listed “gender” incorrectly submitted into the EMR?

But it was the past medical notes contained within the patient’s file that created the most confusion. One note dated a month prior referred to the patient as “she” or “her” throughout its entirety while the following note identified the patient as a “he” or used the word “him” throughout its dictation. In fact, each note almost perfectly alternated from one to the next using those fundamentally different pronouns without any consistency.

Reviewing a patient’s chart before entering the room, which is always done by any MD before appointments or situations like ours, consults or Emergency Room visits, is intended to provide a quick overview of the patient’s medical history and his or her (or their) pre-existing medical conditions as well as any pertinent past surgical history, family history, and medication history. In our case, our patient’s family history was uncommonly absent from his/her/their chart and none of the notes, from either nurses or physicians, could clarify whether our patient was genetically male or female let alone if he or she had undergone any hormone replacement therapy.

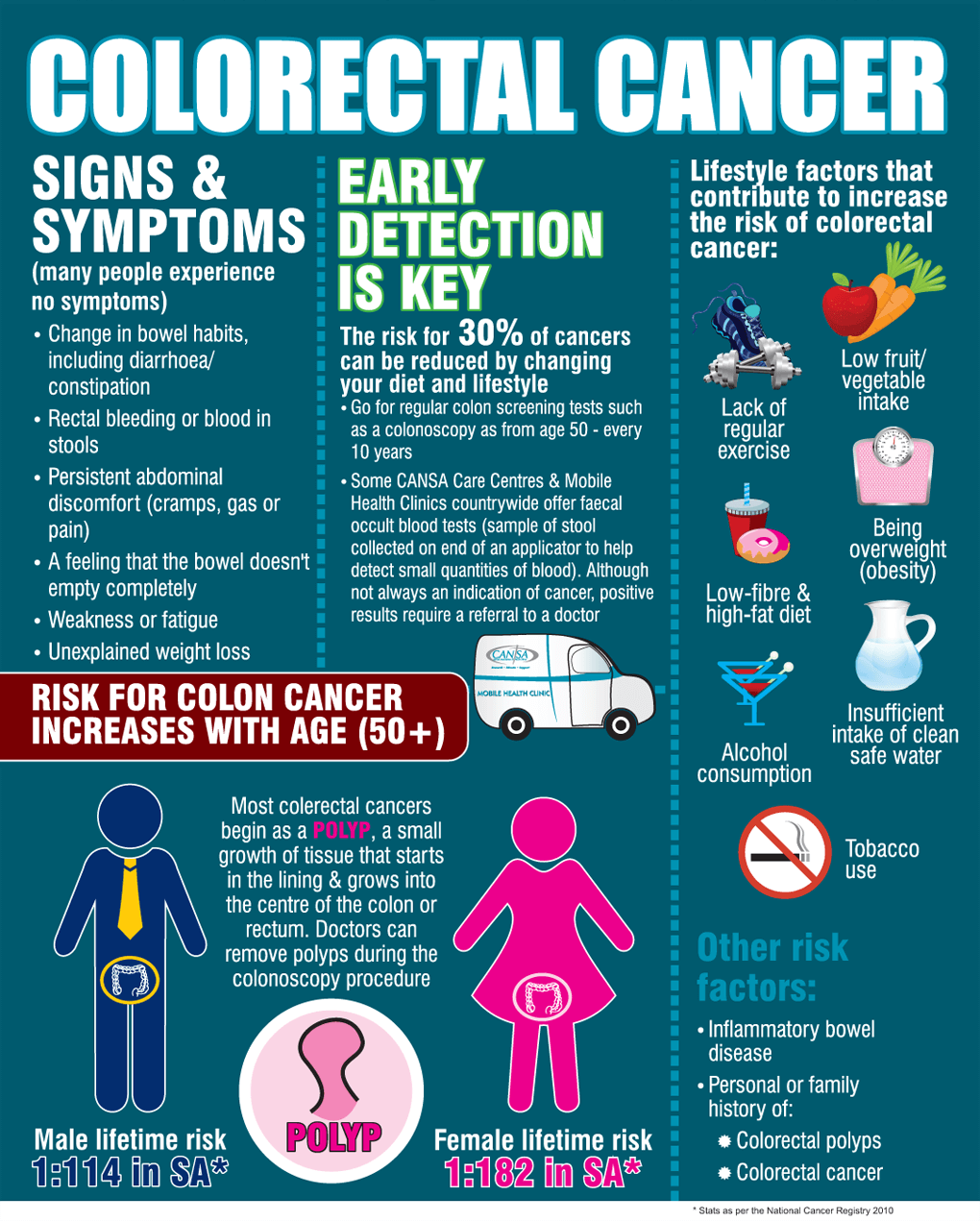

Importantly, when examining a patient with abdominal pain it is crucial to read through the patient’s chart prior to the visit to see if he or she has any family history of inflammatory bowel disease or, even more seriously, colorectal cancer. MDs also scan for any medication taken by the patient that may cause abdominal bleeding, if he/she/they have ever undergone a colonoscopy, or if he/she/they have been the subject of any form of abdominal surgery in the past.

So we were about to walk into the patient’s room empty-handed. Ridiculously, it might have been better if we hadn’t even reviewed the parient’s chart ahead of time—a thought that very rarely occurs among MDs. A patient’s chart is usually majorly helpful in assessing the situation before the patient interview in order to zero in on the most likely cause of the patient’s condition, to provide the best services possible in the shortest amount of time.

We pulled back the easter-egg blue curtain and introduced ourselves. My resident was the night-shift surgeon and I was the third-year medical student that would be in the room as well during the encounter if it was okay with the patient. The patient smiled and said it was fine. In the rush to get to the ER, she looked tired, disheveled, and kept adjusting her wig with a hint of embarrassment and a troubling sense of anxiety: anxiety about her appearance and I think nervousness at how she might be treated by us as a result.

My resident’s anodyne demeanor and tone eased the patient’s tension and it was palpable. I watched my resident with both admiration and sincere deference. I had always looked up to this resident–she was one of my favorites–but it was this encounter alone that made me, almost, idolize her for her compassionate approach to an otherwise anxiety-provoking situation, for both us and the patient. She did what all MDs should do; she smiled and made eye-contact with the patient–not in some forced way but in true sincerity, seating herself down next to the patient’s bed so her eyes were level with those of our nervous patient’s, which kept shifting from the floor back up to her face with hesitation. My resident leaned in and this seemed to focus the patient’s sad eyes on her face. “What was going on?” my resident asked her. What brought her in tonight?

Her eyes focused on the floor below the examination table: Every now and then a severe stabbing pain would awaken her at night and she’d be forced to take the jolting bus to the ER, bearing the cold frost of Cincinnati winters, which, understandably, only exacerbated the already unbearable collywobbles, to sit for hours in horrible discomfort in the bright glaring lights of the ER waiting room. Our patient explained that she didn’t have much money and didn’t own a car. She couldn’t remember the last time she had seen a physician outside of the ER because she was uninsured and couldn’t afford the visits. Her eyes shifted around the room as she spoke of the diarrhea she would experience after the onset of the pain. And of course this made the journey on public transport even worse. My resident nodded with a look in her eyes of genuine empathy. Did she have any other chronic medical issues? Had the cause of the pain ever been diagnosed by anyone before? No. They could never figure out what was wrong. They kept suggesting a colonoscopy but she had never been able to successfully follow through with any scheduled procedure since any colonoscopy performed at any hospital requires a chaperone–to drop you off and return to pick you up once the ordeal was finally over. And she didn’t have any family or close friends with a car who she could ask. The hospital wouldn’t allow her to take a bus or cab. What was she to do? My resident nodded in genuine understanding, saying, without words, that these policies made it difficult for many to receive these important screening procedures.

Next my resident wanted to know, what was her past medical history? Had she ever been diagnosed with a chronic illness?

And at this juncture in the conversation the words which had finally begun to flow freely ebbed and became more forced and uncomfortable.

It was clear to us from our initial step into the small, fusty ER room–barred from the main lobby by a flimsy curtain, loud from the hustle and bustle of ER doctors moving from room to room outside and the sound of medical machines working fastidiously in rooms adjacent to ours–that the patient had been born “male, XY,” many years ago and was, probably for years, trying to transition to “female, XX”. It was clear since pulling the curtain back and introducing ourselves that this was the cause of all the discrepancies on the electronic records we had studied before meeting the patient ourselves. It was clear when the conversation took the turn towards her past medical history that she had most likely experienced negative reactions from her past treating MDs and she was reluctant to open this door, which might morph into a floodgate spilling in waves of additional pain for her yet again.

So my resident continued with caution and care. Her posture, facial expressions, and active listening alone were anodyne nonverbal reassurances. Our guarded patient eased up a bit. Slowly we were able to extract some information about her medical and family history that proved to be hugely significant.

Thus far we had gathered that she was a 54 year old Caucasian “male,” that is born with one X chromosome and one Y, who was in the process of transitioning to female, that is what her notion of female is, with a past medical history of abdominal pain and a family history significant for colorectal cancer. Her father had recently passed away from colorectal cancer and her younger brother had recently been diagnosed with the same terminal disease. Of note, the patient had never received a colonoscopy or rectal exam in the past due to her financial situation which had made access to medical care difficult. She had not yet began hormone replacement therapy.

What was difficult to explain next was that although the patient identified as female, the fact that she was born male with those XY chromosomes predisposed her to colorectal cancer. Men are more likely to develop colorectal cancer than females. Hence, men are medically directed to undergo colonoscopies every 10 years beginning at age 50 but even earlier, at age 40, if they have a family history of colorectal cancer.

It was likely an amalgamation of varying factors that predisposed this particular patient to developing colorectal cancer: she was over 50, she had a family history of colorectal cancer, she had never undergone any type of screening for colorectal cancer, and she had limited access to healthcare and medical services. But, importantly, these predisposing factors were further compounded by the fact that she was born male, was transitioning to female, did not know that being born male—whether she identified as one or not—made her much more likely to develop colorectal cancer, and the overarching realization that the MDs who had seen her in the past were too uncomfortable to broach this topic with her was evidenced by the discrepancies permeating the medical notes regarding her past care that had initially confused us. While those notes may not have been intentionally captious they befuddled a medical record that could have otherwise been straightforward and efficiently thorough.

I sympathized with this patient because I can imagine that, throughout every medical encounter she had experienced, she was reminded that she was born male. Since I have not experienced this disillusionment with my own self myself—in this same regard—I can only surmise that it made her even more reluctant to seek medical care.

All physicians should be not only willing but eager to engage transgender patients in discussions like those we had with this patient that night. It saddened me that, since we were called from the surgery department for a mere consultation, there would be no follow-up with this patient from our end. The resident I was with so empathetically connected with this patient that I hoped this patient would find a similar physician, family practice or internal medicine who she could see regularly, who would be able to follow-up with her and track her medical care. Who would listen and would try to imagine the difficulties she has faced in tackling this unavoidable conflict between her XY chromosomes and the gender she internally identified with.

But just as it is important for physicians to understand patients from their perspective, from their life experiences, and from their internal struggles, I must emphasize that it is equally important for patients to do the same. I hope soon that the stigma surrounding transgender issues dissipates. I think when it does, transgender individuals will be more accepting of the fact that even though their genetics have dictated their medical, anatomical development, these chromosomes do not need to dictate their identity or life choices. They can accept that they are an XY or XX individual but happen to be female or male in their daily lives, respectively.

I think this acceptance is important for both physicians and patients. Because avoidance of these talks, either because the physician is too uncomfortable to touch on these topics or because the patient fears judgment, only hinders the best possible, effective and efficient medical care for them.

If the execrable medical charts had been instead clear that this was a genetic male who transitioned to female, if the patient had been aware of these risk factors and accepted those XY chromosomes as part of their identity—not their gender identity but their genetic makeup, if her past physicians had explained these risk factors to her, the two hours it spent my resident and I would have been used instead to tackle the most concerning medical issue for this patient–one that might have threatened her life. We would have been able to openly discuss the next steps with total acceptance and understanding. Instead, previous MDs who had seen her had taken a crabwise approach to discussing her transgender status and this only put this patient at an even further disadvantage than she already was medically speaking.

Since this experience, I’ve thought about how this might be avoided in the future. The stigma will not disappear overnight but what can the medical community do to speed up this process? At least as far as optimal medical care is concerned.

Perhaps instead of listing a patient in medical charts as:

Joffrey Baratheon, DOB: 1/1/1000, XY

EMRs can instead make a minor adjustment to inform physicians of both the patient’s medical and emotional state at the time of treatment:

Why not:

Joffrey/Jessica Baratheon, DOB: 1/1/1000, XY/FEMALE

The first two letters identifying the patient’s genetic chromosomes—chromosomes that can never be modified regardless of hormone replacement therapy. Chromosomes which should be embraced by patients and physicians alike as part of one’s identity—part being the operative word. These chromosomes don’t define the individual. But they are part of any human being as much as the heart or brain is. XY or XX doesn’t make one “male” or “female.” It merely denotes which specific hormones affect one’s development.

In contrast, the designation “male” or “female” following the slash could symbolize an individual’s “true” identity, that is the gender they personally identify with the most. XY/female will denote to a physician that this patient born with one X chromosome and one Y chromosome has developed with a higher level of testosterone, among other hormones, regulating much of their growth for a significant amount of his or her life, much more so than those born with two X’s and no Y.

For nonbinary patienrs my suggestion is to use the letter Z. A patient with an EMR that displays XYZ will denote that the patient was born with one X chromosome and one Y chromosome. But Z is the non binary identify they feel closest to–neither male nor female. XYZ: someone born “male”–a societal label–but who identifies as neither gender. XXZ: someone born female but who, again, identifies as neither female nor male.

It is important for individuals to embrace their genes without shame. Two X chromosomes or one X and one Y chromosome doesn’t define one as male or female. XX is NOT equivalent to societal notions of females nor does XY specify what we interpret as male. The existence of these chromosomes and the idea of gender identity are incommensurable. XY or XX does not make one “male” or “female” in the conventional societal notions of the words; how one chooses to identify is his or her or their sole choice to make. No chromosome defines the sense of gender.

GENDER IS AND SHOULD BE SEPARATED FROM SEX. BOTH PATIENTS AND PHYSICIANS SHOULD ACKNOWLEDGE THIS DIFFERENCE.

Nevertheless, it is important to embrace these chromosomes as part of one’s identity–not necessarily gender identity but genetic identity because these chromosomes are and will forever be a part of any individual’s medical fingerprint. And for physicians, this relabeling of a significant “identifier” in medical records will only lead to broader understanding and expanded acceptance of individuals and thereby patients. Because EMRs can and should change how they “identify” patients. The more prevalent this becomes the less frequent it will become for an intern to page a senior resident laughing about a confusing medical chart; because it wasn’t the medical chart he was laughing at, it was the patient. By expanding how we “identify” patients in a medical chart we are improving medical care for transgender individuals. These individuals struggle with explaining their identity to others on a daily basis that a device as simple as an electronic medical chart does not need to make his or her or their process of gender-identification even more challenging for these individuals–by doing this we are constructing further obstacles for transgender patients instead of abolishing them.

By misidentifying patients on medical records, physicians are in fact exercising calumny in its highest degree. The burden of guilt for not undergoing a routine screening such as a colonoscopy then falls on the patient when in actuality the burden should fall on physicians who fail to explain the role hormones associated with these chromosomes play during development, who fail to adequately demonstrate the difference between genetic blueprints and gender identity, and who hide within their own zone of comfort because of societal stigma they vowed to disregard when taking an Oath upon entering medical school, an Oath to help others to the best of their ability achieve a life of health regardless of a patient’s “societal status.”

Whether one is born or identifies as XX, XY, XX/male, XY/female, XXZ, or XYZ all individuals are both similar and unique. We all have risk factors that when collated make us unlike any other human being alive. The snowflake cliche is overused but perhaps it is relevant here. We are all different. Let’s acccept our differences while also embracing them. This is what medicine has always been about: seeing the similarities but also the differences and using knowledge to tailor treatment so each patient has as best of an equal chance at a healthy life as possible. That is the duty of physicians and it is also our duty as humans to acknowledge and accept ourselves and others while not only accepting our differences but openly and freely embracing them.

Another addition to the “snapshot” demographic information listed at the top left corner of Epic medical charts should be “he,” “she,” or “they”–the pronouns by which the patient prefers to be identified.

An article published by the Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association (JAIMA) includes the following:

Transgender patients have particular needs with respect to demographic information and health records; specifically, transgender patients may have a chosen name and gender identity that differs from their current legally designated name and sex. Additionally, sex-specific health information, for example, a man with a cervix or a woman with a prostate, requires special attention in electronic health record (EHR) systems. The World Professional Association for Transgender Health (WPATH) is an international multidisciplinary professional association that publishes recognized standards for the care of transgender and gender variant persons.

Transgender people experience their gender identity as different from the sex which was assigned to them at birth. They may seek medical care such as hormone therapy or surgery to effect changes in their secondary sex characteristics toward those of the gender with which they identify, as part of a process referred to as gender transition. It should be noted that the terms ‘sex’ and ‘gender,’ while often used interchangeably, have specific medical and psychological meanings that may differ from general social—or even legal—usage. ‘Sex’ commonly refers to one’s physical sex characteristics (eg, facial hair, body fat distribution, breasts), whereas ‘gender’ represents one’s identity and self-image. ‘Gender transition’ can be thought of as the process through which one aligns one’s physical sex (through hormones, surgery, etc) with one’s gender identity, keeping in mind that not all transgender people will seek a medical transition but may simply focus on a social one; for any given individual, transition may or may not have a specific ‘end point’ and may represent a continued state of flux and exploration that varies by the individual.

From the same article:

In addition to concerns about demographic information such as listed versus preferred name, gender, and pronouns, providers require a means to maintain an accurate record of what organs a patient may or may not have; this record cannot be limited or defined by the patient’s assigned or apparent sex/gender as entered into the EHR. For example, a patient may have been assigned female at birth, and have transitioned to male through the use of testosterone and surgical removal of the breasts; they may also have obtained a court ordered name and sex or gender change and are registered in the EHR system under a male name and gender. However, since this patient still has a cervix, ovaries, and uterus, health care providers will require the ability to enter pelvic exam findings and gynecologic review of systems, and to order a cervical pap smear within the EHR system. EHR products that restrict or pre-populate an individual encounter with sex-specific history, exam, or ordering templates will prevent this patient’s provider from accurately and efficiently documenting their care.

As another example, a patient may have been assigned male at birth and have transitioned to female through the use of estrogen; however, this patient has not yet changed her government-issued identity documents and is currently listed with a male name and sex or gender. The patient has an outwardly female appearance and wishes to be referred to using a feminine name and pronouns. The patient also has breasts as a result of their hormone treatment and will require a breast examination and ordering of a mammogram. An EHR system should guide the administrative and clinical staff to use the patient’s chosen name and pronoun, which should serve to improve patient engagement and comfort while improving retention in care. An EHR system should also allow the provider to document a breast examination and order a mammogram—even though the patient remains registered as male.

The article concludes with several recommendations:

- It is recognized that the overwhelming majority of patients are not transgender, which has led to implementation of a binary male/female oriented system across multiple platforms such as EHR systems, billing and coding systems, and laboratory systems; however, this structure inhibits the collection of accurate medical information, and therefore such systems should be modified.

- Preferred name, gender identity, and pronoun preference, as identified by patients, should be included as demographic variables (such as with ethnicity). These would be captured in readily amendable, optional fields that are separate from the patient’s state-listed name and sex or gender designation, which may continue to be used for billing purposes in circumstances when the patient has not yet obtained legal change of name and/or sex or gender designation. Note that some patients may identify as ‘genderqueer’ and prefer the use of neither pronoun. While lists of current common gender identities, sex options (Table 2), and pronoun options (Box 1) are provided, ideally field parameters would be easily amended to reflect changing paradigms and social trends within transgender communities.

- Provide a means to maintain an inventory of a patient’s medical transition history and current anatomy. An anatomical inventory would allow providers to record into the chart (and/or update as needed) the organs each individual patient has at any given point in time; this inventory would then drive any individualized auto-population of history and physical exam templates. This inventory should be uncoupled from the patient’s recorded gender identity, assigned sex, or preferred pronouns. A list of recommended organs for inventory in transgender patients appears in Box 2, and commonly sought treatments and procedures which may not be listed in current systems but should be included as selectable items in the medical or surgical history, appear in Box 3. The following non-exhaustive list of procedures are not transgender-specific procedures and are omitted from Box 3 as they are already listed in existing systems: hysterectomy, oophorectomy, vaginectomy, orchiectomy, breast augmentation. These procedures, however, also should also be un-coupled from any gender-coded template so that an individual coded as male who has had a hysterectomy, for example, could have that history documented. In addition, sex-specific organ procedures and diagnoses relating to these organs should be un-coupled, so that (as an example) a prostatic ultrasound may be ordered on a patient registered as female, or a cervical pap smear ordered on a patient registered as male. Such practices would allow enhanced decision support for transgender-specific care, such as medication interactions, organ- and sex-specific preventive health alerts, or accommodations for sex-specific laboratory normal value ranges. For example, a patient with a female birth sex and male gender identity, currently registered as a female, who is taking testosterone, may have a hemoglobin of 17 g/dl flagged as ‘high’ by the interfacing laboratory system. A local flag driven by the patient’s birth sex, gender identity, and current testosterone prescription could alert clinicians to reconsider this ‘high’ flag and review laboratory male reference ranges.

- The system should allow a smooth transition from one listed name, anatomical inventory, and/or sex to another, without affecting the integrity of the remainder of the patient’s record. It should be noted that, in some cases, changes in name and sex or gender designation of record will come at different times, and that in some jurisdictions official recognition of a change of sex or gender designation is not possible.

- A system should exist to notify providers and clinic staff of a patient’s preferred name and/or pronoun (if either or both of these differ from the current legal documented name/sex). Systems should include an easily recognized notification or alert flag which appears at a time most consistent with the end-user’s workflow (figure 1).

JAIMA concludes in its article that:

As the care of transgender patients moves into the mainstream, the medical informatics field will be asked to respond to the unique needs of this demographic through the implementation of more accurate and appropriate data collection methods in a range of products and systems. It is hoped that these user-driven recommendations will better inform health information technology research and EHR vendors on the specific needs of transgender patients in this context. Future research should aim to explore current practices among both clinicians and vendors; ultimately this information would be used to drive developer implementation of feasible models which satisfy the recommendations presented here.

See the link at the bottom of this post for the entire article.

Let’s do away with desultory patient identifiers in favor of one’s that live up to modern-day expectations and realities. Peremptory rejection of improving EMRs will be disastrous. Physicians should take the first step ex cathedra in promoting the rights of transgender individuals, including equal access to optimal medical services and education. MDs should be societal leaders and the fact that EMRs still display such glaring discrepancies is incontrovertible evidence that physicians, in regards to transgender rights, are falling behind their responsibilities. Physicians should be the penultimate examples of meliorism.

XX/XY, XY/XX, XYZ. These are the retronyms we should be adopting as we advance towards an all inclusive society and medical system. We all know the alphabet by now. Let’s all begin to sing along together—in harmony.