My grandfather used to have a crude, erring on vulgar, blunt, but charming sense of humor. The stiff and frigid demeanor football fans remember him for, from the 1970’s-1990’s on the sidelines as an NFL head coach, as he scrutinized without expression his football players from kickoff to the last seconds of the fourth quarter, with his arms crossed tightly across his chest, while viciously chewing a piece of gum, his stark blue eyes sharply focused only on the field, shadowed by an intimidating set of eyebrows, stands in stark contrast to his tone at home. During the game he masked his thoughts with an unfaltering pokerface; he never let a quick smirk slip across his face or his posture slump. He wanted to be seen as the tough, takes no shit from anyone, head coach and his portrayal of this during games was impeccable. Never a chuckle or smile–he was definitely not a Pete Carroll. But in locker rooms, at the parties after the games, with colleagues, and even with his own football players (to a degree) he was personable and charismatic. “Chuck Knox was the best coach I ever had,” said one of his former Rams players, Tom Mack, a Hall of Famer. “He always took the time to know each player well enough that he could talk to each player and hit their hot buttons. I never saw another coach like that.” So, while in the locker room, he was tough but loved, during games the fans mostly saw an austere coach with meticulous focus and dedicated persistence.

But at home he wasn’t that tough, intimidating coach. He was Pop-Pop, full of sharp dad jokes and witty cliches–not the Knoxisms he was known for but punny humor that would make us roll our eyes. He was always trying to make us laugh. And even if we didn’t, he would. He’d always chuckle after delivering a line and was always trying to be the funny Pop-Pop for my sister and I–embarassing us whenever there was an opportunity to do so. Not the Chuck Knox who, with 8 simple words, admonished 300 pound 6-foot tall Cortez Kennedy to get out of his office when the Tez mouthed back one day: “Get out of my office right now Cortez,” as quoted by Kennedy himself during his induction into Pro Football’s Hall of Fame.

No we didn’t see that growing up. I grew up with the Chuck Knox who was my Pop Pop that took me for golf cart rides and would surprise us by stepping on the cart’s horn button, located on the floor next to the brake pedal unbeknownst to us, “beep beep” causing us to shriek “where’d that come from Pop-Pop?” He’d just chuckle. Or musically reciting “open sesame” in a mysterious tone when we got to the gate that led to my grandparents’ home, and magically the gate would open. Our mouths would be open: “Pop Pop how did you do that?” “Magic,” he’d chuckle. The remote to the gate, I later learned, would be tucked out-of-sight in his pant pocket. But in high school I became that socially anxious teen and would duck below the windows when he came to pick me up in his tan Cadillac; I didn’t want any classmates seeing me in this horrible vehicular choice. It just screamed elderly uncoolness, even though looking back I’m sure many dads or football fans would have proudly ridden front seat of that car.

My grandpa’s chuckle–one that is so recognizable it should be called the “Chuck”-le–used to resonate from deep within his chest and was a perfect rendition of the ubiquitous “he he” texts we now send. He was always “Chuck”-ling. But he doesn’t anymore.

Read on to learn about various forms of dementia, and the type my grandfather has, or skip ahead if uninterested in the details of dementia’s wide-ranging presentations.

Dementia is not the equivalent of Alzheimer’s. Just as a square is a type of rectangle but a rectangle is not a square, Alzheimer’s Disease is a form of dementia but dementia is not necessarily Alzheimer’s.

And this is the case in a significant amount of patients to warrant discussion. Most MDs, from my experience, are too exhausted, too sleep-deprived and time-constrained, to explain the varied presentations of dementia. After all, they only have, on average, 30-45 minutes to review a patient’s chart, enter that staged examination room, and jump straight to the point: discuss any new symptoms, review the patients meds, prescribe any new meds, word the pros and cons of each pill in a way the patient (or his/her caregiver) understands, write the script, schedule a follow-up, followed by 15 minutes of hastily summarizing the visit in the electronic medical record system, the notes of which are always subject to higher review. There’s not much time for chit-chat let alone medical lessons.

So here’s what you should know about dementia: it’s widely diverse manifestations and underlying pathologies. Don’t worry, I’ll leave out as much medical jargon as possible.

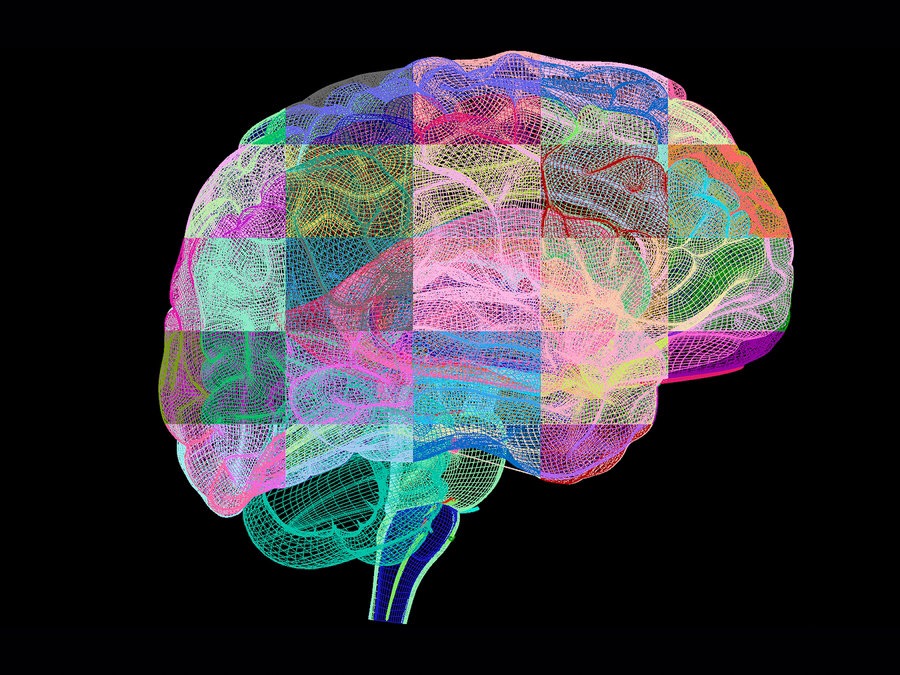

First, let’s review what we know to date about the brain and it’s basic machinery. The brain can be broken up into specific areas and each area serves a distinct purpose. Nevertheless, while the parts of a car can be separated, a motor vehicle cannot function if one piece of machinery is missing, or if the wires have been cut. Because the car won’t be able to start unless its parts communicate with each other, through these wires, to allow for the engine to start, the radio to blast, and the brakes to halt the car’s forward momentum if a threat appears. The brain operates similarly. It’s a team effort that enables us to remember the names of our closest friends, what time we need to make that appointment, and recognize the feeling of fear when walking alone at night and faint footsteps, close behind us, trail our path. Collaboration is key to any meaningful bodily or cognitive action and impulse. And just like a car, while communication is key, each piece of machinery serves an essential purpose. The brain, composed of disparate lobes and structures, is constructed similarly. While car parts can be stolen and sold, they won’t be valuable unless wired into a car complete with all the remaining parts. So, fundamentally, the brain is useless when a lobe is damaged or its wiring is cut. The brain must be complete with all functioning lobes and structures wired together to form a circuit in order for the brain to be whole, capable of effective execution of purposeful action.

Wiring together the individual sections of the brain during infantile and adolescent growth is crucial to producing efficient and effective actions, decisions, thoughts, and, ultimately, a useful human being able to function properly–eat, laugh, socialize, correctly interpret the intent of others’ words or the subliminal message conveyed through facial expressions, develop relationships, reproduce, parent, cope with life’s ups and its downs, grieve, deny, challenge, accept, and prepare for our own disappearance from the world our brains built.

An abnormality in one area of the brain has a limited impact on one of these abilities–including speech and memory–specific to its assigned role in the circuitry that affords the brain as the body’s most powerful organ.

The lobes of the brain:

- Frontal: thinking, memory, behavior, personality, decision-making, movement

- Temporal: hearing, learning, emotions

- Parietal: language and touch

- Occipital: eyesight

Two anatomically and structurally separate formations that are critical to brain function are the brain stem and the cerebellum. You can think of these structures as similar to the pit of a peach: the peach is anatomically partitioned into pit and the pulp. And the pit can easily be removed before consumption. So we have other structures aide the brain in functioning prosperously:

- Brain stem: breathing, heart rate, temperature

- Cerebellum: balance and coordination

In the temporal areas of the brain reside the amygdala and hippocampus, cognitive “organs” that are embedded within the brain:

- The Amygdala: nuclei within the temporal lobes important for memory, decision-making, and emotional reactions as part of the limbic system (don’t worry about this medical term–just remember that it’s our brain’s emotional wiring system.)

- The hippocampus: located in the temporal lobes, functions within the limbic system, and is important for short-term and long-term memory (in Alzheimer’s Disease the hippocampus is the first area of the brain to suffer damage.)

OK so now–before I forget—back to dementia:

Alzheimer’s Disease

Most common type of dementia; accounts for an estimated 60 to 80 percent of cases.

Symptoms: Difficulty remembering recent conversations, names or events is often an early clinical symptom; apathy and depression are also often early symptoms. Later symptoms include impaired communication, poor judgment, disorientation, confusion, behavior changes and difficulty speaking, swallowing and walking.

Brain changes: Hallmark abnormalities are deposits of the protein fragment beta-amyloid (plaques) and twisted strands of the protein tau (tangles) as well as evidence of nerve cell damage and death in the brain

Vascular Dementia

Previously known as multi-infarct or post-stroke dementia, vascular dementia is less common as a sole cause of dementia than Alzheimer’s, accounting for about 10 percent of dementia cases.

Symptoms: Impaired judgment or ability to make decisions, plan or organize is more likely to be the initial symptom, as opposed to the memory loss often associated with the initial symptoms of Alzheimer’s. Occurs from blood vessel blockage or damage leading to infarcts (strokes) or bleeding in the brain. The location, number and size of the brain injury determines how the individual’s thinking and physical functioning are affected.

Brain changes: Brain imaging can often detect blood vessel problems implicated in vascular dementia. In the past, evidence for vascular dementia was used to exclude a diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease (and vice versa). That practice is no longer considered consistent with pathologic evidence, which shows that the brain changes of several types of dementia can be present simultaneously. When any two or more types of dementia are present at the same time, the individual is considered to have mixed dementia.

Dementia with Lewy Bodies

Symptoms: People with dementia with Lewy bodies often have memory loss and thinking problems common in Alzheimer’s, but are more likely than people with Alzheimer’s to have initial or early symptoms such as sleep disturbances, well-formed visual hallucinations, and slowness, gait imbalance or other parkinsonian movement features.

Brain changes: Lewy bodies are abnormal aggregations (or clumps) of the protein alpha-synuclein. When they develop in a part of the brain called the cortex, dementia can result. Alpha-synuclein also aggregates in the brains of people with Parkinson’s disease, but the aggregates may appear in a pattern that is different from dementia with Lewy bodies.

The brain changes of dementia with Lewy bodies alone can cause dementia, or they can be present at the same time as the brain changes of Alzheimer’s disease and/or vascular dementia, with each abnormality contributing to the development of dementia. When this happens, the individual is said to have mixed dementia.

Frontotemporal Dementia

Includes dementias such as behavioral variant FTD (bvFTD), primary progressive aphasia, Pick’s disease, corticobasal degeneration and progressive supranuclear palsy.

Symptoms: Typical symptoms include changes in personality and behavior and difficulty with language. Nerve cells in the front and side regions of the brain are especially affected.

Brain changes: No distinguishing microscopic abnormality is linked to all cases. People with FTD generally develop symptoms at a younger age (at about age 60) and survive for fewer years than those with Alzheimer’s.

Briefly, for completeness, Parkinson’s Disease produces dementia symptomatically similar to Lewy Body Dementia. There are several other lesser-known types of dementia: Huntington’s Disease, Wernicke-Korsakoff Syndrome (the most interesting, in my opinion,) and Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease among others.

So patients with Lewy Body Dementia behave differently than patients with Alzheimer’s disease but similarly to those with Parkinson’s disease and it’s all explained by the underlying damage to the brain. Lumping all memory-deficit diseases together into a single category of “dementia” or assuming all patients with dementia have Alzheimer’s is hugely errant and detrimental to both patients and their caregivers since each type must be managed markedly differently. Further, caregivers should know which type of dementia their loved one or patient has in order to know what to expect.

I am the product of two very dissimilar families: football/sports and the highest level of education, consisting of doctors and lawyers. So, for a long time the Knox family, my mom’s side of the family who has no medical education, ignored the progressive decline in my grandather’s mental state–they wrote it off as simply age-related forgetfulness. Until he left $1000 in cash on the table of an NFL monthly alumni event and a month or so later crashed that beige Cadillac into another car while making a simple left turn at a minor four-way intersection. That’s when they started to listen to my father’s medical remarks and opinion.

My father, a family practice physician, has witnessed my grandfather’s mental decline from afar, as my parents divorced when I was 13 and my grandfather’s mental disabilities didn’t manifest until I was 16 or 17 years old. It wasn’t until my Pop-Pop made that error in judgment to turn left into oncoming traffic in his Cadillac that my grandmother took action, permanently revoking his access to the car keys. He still could drive the golf cart though, she gave him that–he didn’t have dementia, she said, it was just “age.” Even at 16 I didn’t agree with her “diagnosis.” I argued repeatedly with her: “he needs to see a doctor Mimi. He might have Alzheimer’s”; I didn’t know at that age the fundamental take-home message of this post that dementia is not necessarily always Alzheimer’s. Regardless, I printed off articles and pages describing support groups and handed them to my Mimi to read but she disregarded them and they ended up in the trash, literally. I think, in hindsight, she was going through the stages of grief as his wife. First, denial. Second, Anger. Third, bargaining. That’s what stage she was at: he couldn’t drive the Cadillac but he could drive the golf cart, he couldn’t drink hard liquor anymore but he could sip wine. She even thought he could still dress himself until it took increasingly longer for him to do so with one memorable occasion being his choice to wear his old Rams tracksuit to dinner at the Country Club, complete with the matching hat. “Chuck! You can’t wear that to the Club! Go back in and put on your Tommy Bahama shirt.” I couldn’t decide if it was total obliviousness or denial.

Then it got worse. And, since I lived with them, I saw the step-wise decline in his memory, speech, personal care, and what MDs call “ADLs” or Activities of Daily Living firsthand. First he couldn’t brush his teeth or shave. Then he couldn’t dress himself. Then he couldn’t use the bathroom by himself. That “Chuck”-le slowly dissipated. Then it was gone.

Finally a research group from UCLA made the trip to La Quinta and delivered their preliminary diagnosis of Lewy Body Dementia. So after years, my grandma’s denial, anger, and bargaining finally shifted. To acceptance.

Before I even enrolled in med school, I educated myself about Lewy Body Dementia. Those shuffling footsteps we used to joke about, “Well, here comes Pop-Pop,” got louder and that suddenly made sense. His gradual stooping posture, no longer that stiff board stance seen on sidelines, made sense. But it was his night terrors that, for me, incited anger in me, directed at my Mimi for not doing something sooner.

Recurrent nightmares, something that had always interrupted his sleep, became much more severe and frequent. I was often awoken in the middle of the night by my grandmother to help her calm my grandfather down as he unconsciously stood next to their bed, his arms raised, fists clenched–he would be reliving a fight from back when he was a teen in Sewickley, Pennsylvania with an abusive alcoholic father to drag home from bars when his mother ordered him to do so. They had no windows in their home they were so poor. No phone. Linoleum floors. And a rough neighborhood where you had to learn to be street-smart and tough to survive until you turned 18 and could finally work in the steel mills or join the army (my grandfather tried when he was 15 but they discovered his age and turned him away.)

The night terrors got worse. My Pop-Pop who used to take me for date shakes and golf cart rides and say to me “if you ever need anything who do you call?” “Pop-Pop” was suffering. And there was nothing I could do but dodge his asleep punches, make sure he didn’t fall–which he often did–and hit his head, and try to get him back to bed, reminding him that he wasn’t in Sewickley anymore. He was in a million dollar house he earned from years of hard work, and he was safe. But it took a lot of convincing and sometimes lasted hours, at 3 or 4 in the morning.

My grandma is a humble, modest, and strong woman. But eventually it was too much for her to handle alone with only help from my sister and I. So, the house my grandfather had built as a final demonstration, mostly to himself, that he had “made it,” a place to retire and live out the rest of his years in peace was sold and they moved; I don’t think his weakened brain was even able to process the transition. A multi-million dollar house, built on two lots and custom-designed and constructed, was traded in for a one-bedroom cottage in Anaheim.

My grandfather used to shoulder all familial responsibilities, which ranged from financial duties to making sure all of us in the family were thriving in our lives, fell to my grandmother who initially didn’t know anything about how to manage these newfound responsibilities. I think she was shocked then confused then overwhelmed–but she never showed it, out of shame would be my best guess since she has never complained and rarely have I seen her cry.

She still hides her emotions from everyone including me and purposefully conceals aspect of my grandfathers’s decline from anyone outside of our family and close-knit circle of friends. In fact, she’d be horrified if she knew I had written this post, especially online. But I don’t blame her. She grew up in a time when mental illness was always hidden and protected privately. At 83 I don’t expect her to suddenly develop the awareness that times have changed. That not only is dementia but mental illness overall is also frequently openly discussed and accepted.

So she continues to “protect” him from what she fears might be “judgment”; she says she wants everyone to remember him for how he used to be and not think of the state he is in now once he is gone. This weight of shielding him away from the public has taken its toll on her. She doesn’t laugh much anymore and my grandfather can now only speak a few sentences at a time–and that’s on good days. She still refuses to embrace the notion that he won’t be remembered for having dementia; even if everyone knew he would still be remembered for being a fucking talented NFL head coach who set records and might even make induction into that Hall in Canton one day.

But I wish she would acknowledge that times have changed and that the vast majority of people–fans, old acquaintances, former staff members–would be accepting of who he is now. They wouldn’t expect that same charismatic sociable Chuck Knox of the 1970’s. It’s ok for him to be around fans; that won’t change how they’ll remember him. Not only would allowing him to leave their gated community every once in a while, under the supervision of his caregivers, or attend an LA Rams game help stimulate his now mostly vacant mind but it would also help others struggling in similar situations with ill family members or friends. But she won’t and I don’t think ever will.

Whenever I visit, his blue eyes regain focus. He always kisses me and he always grabs my hand before I walk away. And he always meticulously whispers, “I love you.” That’s what he says now when I leave. But I know he’s trying to say what he used to always say, “I love you more than anything–you know that.” He recalls, he just can’t remember. The words are there but jumbled and it’s too hard for him to make sense of the mess; like a game of Scramble, the words are there but need to be sorted and made sense of before expressed. I always know what he’s trying to say and my Mimi does too; he’s always trying to tell her how much he loves her.

But, “It’s just too hard,” she says at any suggestion of wheeling him to familiar places or events–like football games. Instead he spends his days in a comfortable chair, pouring confusedly at old pictures, his face un-purposefully expressionless, across from a TV broadcasting a football game.

The laughter is gone but he’s still here. It’s OK for people to know that dementia, in all forms, can impact anyone and their family–even ones who led incredibly public and colossal lives.

Dementia is no laughing matter. But those who are still living with it should not be buried just yet. For the brain and for those who suffer from dementia, isolation is essentially burial.

CTE? Check out my other blog post.