If you haven’t already binge-watched, with reproachfully debasing interruptions from Netflix (“are you still watching?” Your reflection glaring back at you in disappointment,) the cult phenomena that is Stranger Things, you should set aside an hour–or 10–to begin Season 1 of the series before your friends begin discussion of Season 2 over draft beers. For starters, because it’s inexplicably addicting even if you aren’t a sci-fi fan. And secondly because it’s deeply rooted in conspiracist-propagated “true” events that supposedly began in the early 1980’s. I won’t include any spoilers but will delve into the show’s inspiration and foundation: the Montauk Project. In fact, writers pitched the show under the working title “MONTAUK.” But what’s eerier is the show’s mirroring of actual government sanctioned experiments that occurred over the course of several decades: the CIA’s implementation of MKUltra. It’s probably even stranger.

Prepare yourself because both stories–if true–are disturbing, wholly unethical to be modest, and makes you think “fuck if this happened then was 9/11 really a conspiracy theory? Oh fuck what about JFK?” You might consider packing a small lightweight suitcase, putting it under your bed, and carrying your passport in your wallet from now on “just in case.” Then you’ll probably start applying tape over your MacBook’s camera while jacking off to porn and unscrewing all your lightbulbs and demantling your iPhone to search for tiny wiretaps too (OK one spoiler–sorry.) But before you walk yourself into paranoia and a diagnosis of psychosis just yet, take a Xanax (just kidding…but really you should consider getting some) and read on.

The first is another story not unlike Area 51, involving space aliens and outrageous experimentation–all performed on a U.S. military base.

The second details experimentation on human subjects without their consent, government cover-ups, and disappearing documents.

So let me open your curiosity door and let’s learn a little about “Papa”…

THE MONTAUK PROJECT

The Montauk Project was an alleged series of covert United States government projects conducted at Camp Hero or Montauk Air Force Station located on Montauk, Long Island. The project’s purpose was, purportedly, to develop psychological warfare techniques and conduct “exotic” research, including exploring the concept of time travel. Believers say that people were kidnapped at said U.S. Air Force base and subjected to mind control and time travel experiments. And extraterrestrials all actively participated in it.

Clearly nobody has been able to actually prove these allegations and all that’s left of this “Montauk facility,” which is now a state park, are the above-ground remnants of the original Air Force base. According to a document issued by the Air Force Historical Studies office, the Montauk base, then known as Camp Hero, was decommissioned in the early 1980s.

The quaint town of Montauk is a small seaside resort community on the tip of Long Island that draws vacationers to its shores every year. Camp Hero, located a short distance outside of Montauk, has origina as far back as the Revolutionary War, during which it was used to test military cannons. Later, during World War II, Camp Hero operated as a coastal defense installation against any possible Nazi intrusions into America.

Three men, Alfred Bielek, Stewart Swerdlow and Preston Nichols, claim that Camp Hero instead ended up as an underground site for the execution of scientific atrocities and unethical medical experimentation.

Bielek, a retired electrical engineer, maintains he was part of the mysterious Philadelphia Experiment, where in 1943, the U.S. Navy reportedly attempted to assemble a small destroyer undetectable to radar. The test ended in disastrous results, including the ship vanishing from the Philadelphia Navy yard and — “allegedly”– traveling through time.

According to Bielek’s story, he was uprooted, abducted, from Philadelphia, and transported ahead in time. He claims extraterrestrials were responsible for the technology used in this so-called Philadelphia Experiment. He also affirms he was recruited in 1970 to work on mind control and time travel projects at Montauk Facility.

Swerdlow’s story involves being kidnapped as a teenager from his Long Island, N.Y., home, taken to the Montauk base, and subjected to a variety of experiments.

Swerdlow recalls being subjected to horrific experimentation while at the Montauk facility.

“Beatings, a lot of torture, electrical shock, burials, near-drownings,” Swerdlow asserts. “They’d bring you to the point of death, and then they would save you, and the person doing this would be your rescuer or god, and would say, ‘I’m the one that saved you and remember that.’ And that became your handler — your programmer.”

He insists, “The walls were very damp, oozing water, so it appeared to be deep underground or even underwater. I was always on this cold, hard table. Sometimes there’d be other people around, either my age or older, and electrodes were put into me and injections.”

All three men profess to have seen first-hand extraterrestrials while employed at the underground Camp Hero facility.

“Well, there were quite a number of aliens at Montauk,” asserts Bielek. “Some were there on a semi-permanent basis. A lot of them were just visitors that came in and looked at what they wanted to see and went back home. There were little grays there, which I suspected were degenerated humans from out of the future. Large gray aliens (which are a different species) were also at Montauk, and they were highly intelligent.”

Nichols, like Bielek, was an electrical engineer at the time. He says he worked with Bielek in the mind control and psychic aspects of the Montauk Project.

“There were definitely alien beings at Montauk,” Nichols claims. “We had the little grays and the larger grays as well as a variety of reptilian beings. The large grays didn’t want anything to do with me because they couldn’t reach me telepathically. When I entered a room they would leave. They were the strangest thing that I ever saw. At that point, I was beginning to doubt my own sanity.”

And Swerdlow also avows an alien presence at Montauk: “Most of the time my interaction was with human beings, but I did come into close contact with alien beings. I did see, occasionally, intelligent reptilian humanoid beings as well as gray aliens who were once human beings but were physically altered as a result of degeneration and radiation toxins in their system. Most of them communicated with mental telepathy.”

In addition to igniting the flame that is Stranger Things, the myths, or realities, of Montauk Facility have also served as a basis for an upcoming film, “Montauk Chronicles,” written by Christopher Garetano.

Garetano shot much of his project at the actual site of Camp Hero.

“When you walk through the area now, you see this giant, imposing radar tower that still stands,” Garetano told AOL Weird News. “The park currently has strange regulations: You’re not supposed to use any radio equipment there and you are cautioned about unexploded ordnance. While filming my movie here, I couldn’t understand why people are allowed to walk around a park where there are still unexploded devices or why radio equipment isn’t allowed if the radar tower is now defunct and the entire base is completely non-operational.”

That question may be answered by a brochure issued in 2001 for visitors to Camp Hero. It includes a section called Unexploded Ordnance (UXO) Warnings: “Please follow the following steps if you think you have come across Unexploded Ordnance:”

- Never transmit radio frequencies (walkie talkies, citizen’s band radio) near UXO.

- Never attempt to touch, move or disturb UXO.

- Avoid any area where UXO is located.

Garetano has pondered the ordinance’s bizarre warnings, stating it’s “strange that they don’t want you to use radio devices that may set off unexploded bombs, yet they allow the public to walk around a potentially high danger area!”

In addition to the enormous, looming, abandoned radar tower at the Camp Hero site, there are also giant doors, or bunkers, cemented and sealed into the side of various hills dotting the forest area. Also strewn throughout the wooded park are numerous apparatuses that appear to be above-ground manhole covers.

“These are entrances that obviously go down into something,” Garetano stated in the interview. “There are claims from people that these are entrances to underground tunnel systems that ran beneath the military base that allegedly would take you to the true entrance of the facility.”

Among the unusual reports included in the assertions made by the individuals who insist their experience of the Montauk events is a device they called “The Montauk Chair.” According to these alleged participants, a powerful psychic would sit in this specified chair and could then inexplicably materialize objects out of thin air and transform them into physical reality.

After spending countless hours with the men who are the subjects of his film, Garetano says he didn’t always believe their stories and suppositions.

“At first I didn’t. These men have not benefited financially — they didn’t gain anything from this. And they’ve endured ridicule as they maintain their story,” Garetano said.

As for Netflix’s hit show Stranger Things, the creators were inspired by the repressed memories of those who survived the Montauk horrors:

“Described as a love letter to the ’80s classics that captivated a generation, the series is set in 1980 Montauk, Long Island, where a young boy vanishes into thin air. As friends, family and local police search for answers, they are drawn into an extraordinary mystery involving top-secret government experiments, terrifying supernatural forces and one very strange little girl.”

An article published by Thrillist highlights a man named Preston Nichols, who also claims to have memories of being involved in the experiment known as the “Montauk Chair,” which, as I mentioned before, purportedly manifested the ability to initiate and amplify psychic powers.

An excerpt from Nichols’ book “The Montauk Project: Experiments in Time” describes one specific experiment he experienced at the facility:

“The first experiment was called ‘The Seeing Eye.’ With a lock of person’s hair or other appropriate object in his hand, Duncan [Cameron, supposed psychic] could concentrate on the person and be able to see as if he was seeing through their eyes, hearing through their ears, and feeling through their body. He could actually see through other people anywhere on the planet.”

Sound familiar? Do any esoteric mental images come to mind? Maybe an Upside Down portal?

And in this excerpt from Nichols’ book he writes how Duncan summoned a monster while on the chair:

“We finally decided we’d had enough of the whole experiment. The contingency program was activated by someone approaching Duncan while he was in the chair and simply whispering ‘The time is now.’ At this moment, he let loose a monster from his subconscious. And the transmitter actually portrayed a hairy monster. It was big, hairy, hungry and nasty. But it didn’t appear underground in the null point. It showed up somewhere on the base. It would eat anything it could find. And it smashed everything in sight. Several different people saw it, but almost everyone described a different beast.”

MKULTRA

The series Stranger Things also echoes another governmental project–this one indubitably somewhat legitimate, although details vary–known as Project MK-ULTRA, the CIA’s secretive, illegal program. Throughout its operation, the government carried out scientific research on human subjects. During the Cold War, the CIA subjected ill-informed patients to experiments with drugs, most notoriously LSD. Some argue the program was for the sole purpose of mind control.

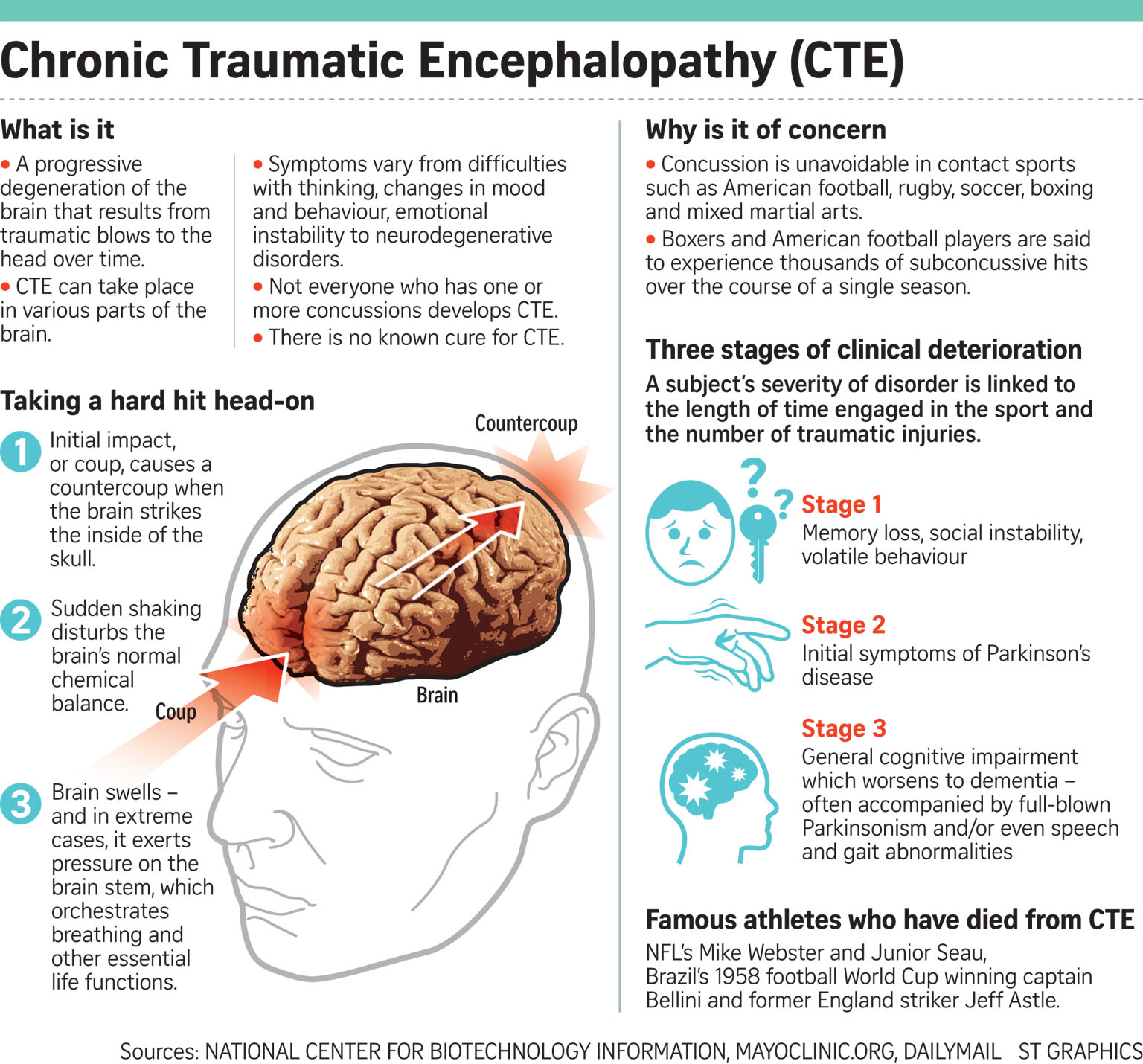

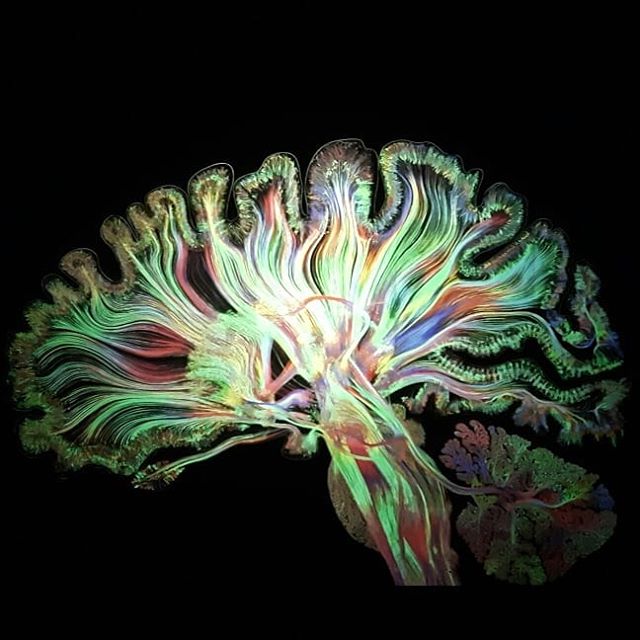

Project MKUltra, also referred to as the CIA Mind Control Program, was the code name given to a program and implementation of experiments performed–at times illegally–on human subjects. The program was designed and enforced by the United States Central Intelligence Agency. The intention of these experiments on humans was to identify and develop drugs and procedures for use during interrogations and torture, so as to weaken the victim to force confessions through “mind control.”

The project began in the early 1950’s and was officially sanctioned in 1953. It was subsequently reduced in scope in 1964, further curtailed in 1967, and officially halted in 1973. The program engaged in an extraordinary number of illegal activities, including the use of unwitting U.S. and Canadian citizens as test subjects, which obviously led to widespread controversy regarding the project’s legitimacy.

MKUltra employed numerous methodologies to manipulate people’s mental states and alter brain functions: the surreptitious administration of drugs (especially LSD) and other chemicals, hypnosis, sensory deprivation, isolation and verbal abuse, as well as other forms of psychological torture.

The scope of Project MKUltra was notably broad, with research performed at 80 institutions, including 44 colleges and universities, and even at multiple hospitals, prisons, and pharmaceutical companies. The CIA operated through these institutions using front organizations. Yet top officials at these institutions were oftentimes aware of the CIA’s involvement. As the US Supreme Court later noted in CIA v. Sims 471 U.S. 159 (1985) MKULTRA was concerned with:

“The research and development of chemical, biological, and radiological materials capable of employment in clandestine operations to control human behavior.”

The program consisted of 149 subprojects, which the Agency contracted out to various universities, research foundations, and other similar institutions. At least 80 institutions and 185 private researchers participated and because the Agency funded MKUltra indirectly, many of the participating individuals were unaware that they were under the direction of the CIA.

Despite the Supreme Court ultimately upholding the CIA’s insistence that sources’ names could be redacted for their protection, it nonetheless validated the existence of MKULTRA to be used in future court cases and confirmed that for 14 years the CIA performed clandestine experiments on humans to study human behavior.

So, between 1953 and 1966, the CIA financed a wide-ranging project, code-named MKULTRA, which was concerned specifically with the research and development of chemical, biological, and radiological materials. These materials were to be utilized in clandestine operations to control human behavior but the existence of Project MKUltra wasn’t brought to public attention until 1975 when the Church Committee of the U.S. Congress, and a Gerald Ford commission began investigating CIA activities within the United States.

Investigative efforts were, however, hampered by the fact that, in 1973, CIA Director Richard Helms ordered all MKUltra files destroyed. As a result, the Church Committee and Rockefeller Commission investigations were forced to rely exclusively on the sworn testimony of direct participants and on the relatively small number of documents that survived Helms’ order that all evidence of MKUltra’s existence be destroyed.

In 1977, a Freedom of Information Act request uncovered a cache of 20,000 documents relating to project MKUltra, leading to Senate hearings in the last few months of the year. Interestingly, in July 2001, some surviving information regarding MKUltra was finally declassified.

As mentioned previously, 44 American universities, 15 research foundations or chemical or pharmaceutical companies, 12 hospitals or clinics, and three prisons are known to have participated in the project that was MKUltra.

In case you were wondering the origins of the project’s intentionally obscure CIA cryptonym. MKUltra is made up of the digraph MK, meaning the project was sponsored by the agency’s Technical Services Staff,) followed by the word Ultra (which previously had been used to designate the uttermost secret classification of World War II intelligence.)

Headed by Sidney Gottlieb, the MKUltra project began on April 13, 1953, on the order of CIA director Allen Welsh Dulles. Its aim was to develop mind-controlling drugs for use against the Soviets, largely in response to alleged Soviet, Chinese, and North Korean use of mind control techniques on U.S. prisoners of war in Korea. The CIA thought the methods were novel ones and hoped to use similar techniques on their own captives. The CIA was also interested in developing the capacity to manipulate foreign leaders with such techniques and would later invent profuse schemes in order to intoxicate and mentally override Fidel Castro.

Experiments were too often conducted without the subjects’ knowledge or consent. Further, many academic researchers who were funded through grants from the CIA’s front organizations were unaware of the manipulative purposes of their work.

The project’s quintessential goal was to produce the ideal “truth drug” to use during the interrogations of suspected Soviet spies during the Cold War. However, the program’s intentions generalized to explore any other possibilities of human mind control.

Because most MKUltra records were deliberately destroyed in 1973 by order of then CIA director Richard Helms, it has been difficult, if not impossible, for investigators to gain a thorough and definitive understanding of the more than 150 individually funded research sub-projects sponsored by MKUltra and other related CIA programs.

Returning to the project’s birth, MKUltra materialized during a period of, what Rupert Cornwell described as, “paranoia” within the CIA; the U.S. had lost its nuclear monopoly and fear of Communism was at its height. James Jesus Angleton, head of CIA counter-intelligence, postulated that the organization’s protective shell had been infiltrated by a mole at the highest level.

So, the CIA poured millions of dollars into studies examining methods of manipulating and controlling the mind to enhance their ability to extract information from resistant subjects during interrogation.

One 1955 MKUltra document gives an indication of the size and range of the effort; this document refers to the study of an assortment of mind-altering substances described as follows:

- Substances which will promote illogical thinking and impulsiveness to the point where the recipient would be discredited in public.

- Substances which increase the efficiency of mentation and perception.

- Materials which will cause the victim to age faster/slower in maturity.

- Materials which will promote the intoxicating effect of alcohol.

- Materials which will produce the signs and symptoms of recognized diseases in a reversible way so that they may be used for malingering, etc.

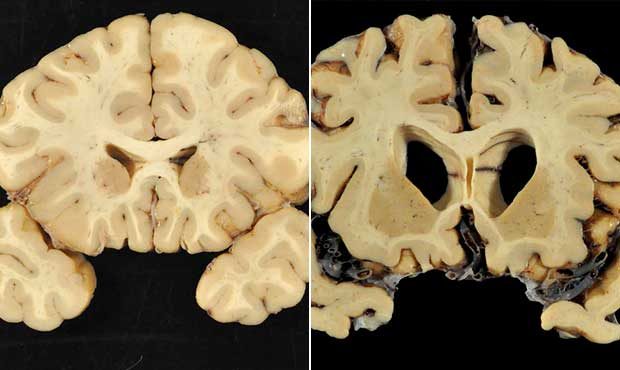

- Materials which will cause temporary/permanent brain damage and loss of memory.

- Substances which will enhance the ability of individuals to withstand privation, torture and coercion during interrogation and so-called “brain-washing”.

- Materials and physical methods which will produce amnesia for events preceding and during their use.

- Physical methods of producing shock and confusion over extended periods of time and capable of surreptitious use.

- Substances which produce physical disablement such as paralysis of the legs, acute anemia, etc.

- Substances which will produce a chemical that can cause blisters.

- Substances which alter personality structure in such a way that the tendency of the recipient to become dependent upon another person is enhanced.

- A material which will cause mental confusion of such a type that the individual under its influence will find it difficult to maintain a fabrication under questioning.

- Substances which will lower the ambition and general working efficiency of men when administered in undetectable amounts.

- Substances which promote weakness or distortion of the eyesight or hearing faculties, preferably without permanent effects.

- A knockout pill which can surreptitiously be administered in drinks, food, cigarettes, as an aerosol, etc., which will be safe to use, provide a maximum of amnesia, and be suitable for use by agent types on an ad hoc basis.

- A material which can be surreptitiously administered by the above routes and which in very small amounts will make it impossible for a person to perform physical activity.

CIA documents indicate that “chemical, biological and radiological” methods were investigated for the purpose of mind control by MKUltra . An estimated $10 million USD (roughly $87.5 million adjusted for inflation) or more was spent in total.

LSD

Early CIA efforts focused on LSD9/589, which later came to dominate many of MKUltra’s programs. The CIA aimed to investigate whether or not they could make Soviet spies defect against their will and whether the Soviets could do the same to the CIA’s own operatives.

Once Project MKUltra officially commenced in April 1953, experiments included administering LSD to mentally ill patients, prisoners, drug addicts and prostitutes, or as one agency officer put it simply, “people who could not fight back.”

LSD, among other drugs, was usually administered without the subject’s knowledge or informed consent, an explicit violation of the Nuremberg Code (a code drafted to establish international human rights laws and signed by the US.)

The aim of administering such medications was to discover drugs which would irresistibly evoke deeply seated confessions or wipe a subject’s mind clean–deleting unwanted information–and subsequently re-programming the individual as “a robot agent.”

Some subjects’ participation was in fact consensual but in these cases they were specifically singled out for even more extreme experiments. In one case, seven volunteers in Kentucky were given LSD for 77 consecutive days.

Eventually, LSD was dismissed by MKUltra’s researchers as too “unpredictable” in its results. They gave up the notion that LSD was “the secret that was going to unlock the universe.” Nevertheless, the drug still remained within the CIA’s arsenal of potential interrogative methods of operation.

By 1962 the CIA and the army had developed a series of “super hallucinogens,” including the highly touted BZ which was thought to hold greater promise as a mind control weapon. This resulted in many academics and private researchers withdrawing their support and ultimately LSD research became less of a priority altogether.

HYPNOSIS

Declassified MKUltra documents prove that hypnosis was studied as early as the 1950’s. Experimental goals included: the creation of “hypnotically induced anxieties,” “hypnotically increasing ability to learn and recall complex written matter,” investigating hypnosis and polygraph examinations, “hypnotically increasing ability to observe and recall complex arrangements of physical objects,” and studying the “relationship of personality to susceptibility to hypnosis.”

Experiments were conducted with drug induced hypnosis and with anterograde and retrograde amnesia while under the influence of such drugs.

DEATHS

Given the CIA’s purposeful destruction of most records, its failure to follow informed consent protocols with thousands of participants, the uncontrolled nature of the experiments, and the total lack of follow-up data, the exhaustive impact of MKUltra’s experimentations on human subjects, including resultant deaths, may never be known.

However some deaths associated with involvement in Project MKUltra’s experimental process have been reported. The most notable case is that of Frank Olson.

Olson, a United States Army biochemist and biological weapons researcher, was given LSD without his knowledge or consent in November, 1953, as part of a CIA experiment. One week later, while still under the influence of LSD, Olson committed suicide by leaping out of a window.

The CIA physician who was assigned to monitor Olson during these “trips” claimed to have been asleep in another bed in a New York City hotel room when Olson exited the window and fell thirteen stories to his death.

In 1953, Olson’s death was declared a suicide following a severe psychotic episode. The CIA’s own internal investigation concluded that the head of MKUltra, CIA chemist Sidney Gottlieb, had conducted the LSD experiment with Olson’s prior knowledge, despite the other men taking part in the experiment later asserting that they had not been informed as to the exact nature of the drug until approximately 20 minutes after its ingestion. The report further suggested that Gottlieb was nonetheless due a reprimand, as he had failed to take into account Olson’s previously diagnosed suicidal tendencies, which clearly might have been exacerbated by the administration of LSD to Mr. Olson.

The Olson family disputes the official version of events. They maintain that Frank Olson was murdered. According to their statements, Olson had become a security risk and was eliminated out of fear he might divulge state secrets associated with highly classified CIA programs, about many of which he had direct personal knowledge.

A few days before his death, Frank Olson quit his position as acting chief of the Special Operations Division at Detrick, Maryland (later Fort Detrick) because of a severe moral crisis concerning the nature of his biological weapons research. Among Olson’s concerns were the development of assassination materials used by the CIA. The CIA’s use of biological warfare materials in covert operations, experimentation with biological weapons in populated areas, collaboration with former Nazi scientists under Operation Paperclip, LSD mind-control research, and the use of psychoactive drugs during “terminal” interrogations under a program code-named Project ARTICHOKE.

Further, ensuing forensic evidence conflicted with the official version of events; when Olson’s body was exhumed in 1994, cranial injuries indicated that Olson had been knocked unconscious before exiting the window. The medical examiner subsequently declared Olson’s death a “homicide.”

In 1975, Olson’s family received a $750,000 settlement from the U.S. government and formal apologies from President Gerald Ford and CIA Director William Colby, though their apologies were limited to informed consent issues concerning Olson’s ingestion of LSD.

On 28 November 2012, the Olson family filed suit against the U.S. federal government for the wrongful death of Frank Olson.

A 2010 book by H. P. Albarelli Jr. alleged that the 1951 Pont-Saint-Esprit mass poisoning was part of MKDELTA, that Olson was involved in that event, and that he was eventually murdered by the CIA. However, academic sources attribute the incident to ergot poisoning through a local baker.

MKULTRA AND INFORMED CONSENT

The revelations about the CIA and the Army prompted a number of subjects or their survivors to file lawsuits against the federal government for conducting experiments without the explicit consent of its subjects, which is required in all medical practice. Although the government aggressively, and sometimes successfully, sought to avoid legal liability, several plaintiffs did receive compensation through court order, out-of-court settlement, or acts of Congress. As previously mentioned, Frank Olson’s family received $750,000 by a special act of Congress, and both President Ford and CIA director William Colby met with Olson’s family to apologize publicly.

Previously, the CIA and the Army actively and successfully sought to withhold incriminating information regarding MKUltra, even whilst secretly providing compensation to the families.

The medical trials at Nuremberg in 1947 deeply impressed upon the world that experimentation with unknowing human subjects is morally and legally unacceptable. The United States Military Tribunal established the Nuremberg Code as a standard against which to judge German scientists who experimented with human subjects. In defiance of this principle, military intelligence officials began surreptitiously testing chemical and biological materials, including LSD through Project MKUltra.

Justice Sandra Day O’Connor wrote:

“As Justice Brennan observes, the United States played an instrumental role in the criminal prosecution of Nazi officials who experimented with human subjects during the Second World War, and the standards that the Nuremberg Military Tribunals developed to judge the behavior of the defendants stated that the ‘voluntary consent of the human subject is absolutely essential … to satisfy moral, ethical, and legal concepts.’ If this principle is violated, the very least that society can do is to see that the victims are compensated, as best they can be, by the perpetrators.”

In separate posts I will discuss the significance of informed consent in medical practice and its development through historical, often atrocious, events.

THE AFTERMATH OF MKULTRA

At his retirement in 1972, Gottlieb dismissed his entire effort for the CIA’s MKUltra program as useless. Although the CIA insists that MKUltra-type experiments have been abandoned, some CIA observers, disturbingly, insist there is little reason to believe it does not continue to operate today under a different set of acronyms.

Victor Marchetti, author and 14-year CIA veteran, stated in various interviews that the CIA routinely conducted disinformation campaigns and that CIA mind control research has in fact continued to remain a governmental experiment. In a 1977 interview, Marchetti specifically called the CIA’s claim that MKUltra was abandoned a “cover story.”

BACK TO STRANGER THINGS

Despite the series’ clear reflection of two separate but not entirely dissimilar apparent events, although the disputed legitimacy of each vary, the creators of Stranger Things, Matt and Ross Duffer, have been strangely coy about any connection the show’s theme has to the Montauk Project (or any other potential government covert experimental operations.) Instead, they have only remarked that ditching the original “Montauk” title was “very painful.”

Sounds strange to me. Have stranger things occurred? Probably. But this is definitely one of the strangest. Scientifically speaking.

What else might be stranger? Winona Ryder and her facial expressions…but that’s off-topic.